From the SEMA Washington, D.C., office

Since early 2025, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), under Administrator Lee Zeldin, has taken an aggressive approach to reducing the regulatory burdens imposed by the agency. The Trump EPA's deregulatory agenda has been aimed at encouraging the re-domestication of American manufacturing, including in the automotive sector, and unleashing America's energy independence and dominance. It's important to understand both what the EPA's deregulation agenda means and what it doesn't mean for the automotive aftermarket industry.

Many of the EPA's deregulatory actions have either undone or significantly modified rules that the EPA issued under previous administrations. These deregulatory actions have largely been taken in response to executive orders issued by President Trump, but they are all limited to the authorizing legislation passed by Congress. As a matter of practice, once Congress passes a bill and the president signs it into law, federal departments and agencies, such as the EPA, are responsible for writing the rules and regulations that specify how they will implement and enforce the law. So, while regulations can generally be repealed, replaced or revised, the laws are still the laws and regulations must be consistent with the framework they establish.

Law vs. Regulation

The Clean Air Act of 1970 (CAA), as amended in 1990, is the bedrock of federal environmental law and policy regarding air emissions. The EPA's tampering prohibition is present in the CAA and explicitly prohibits tampering with or disabling emission control systems, including the manufacture or sale of defeat devices. The EPA's deregulatory actions cannot change this. Only Congress can make this change by passing legislation. Regulations implementing the law, on the other hand, are issued by the EPA, and are subject to change with a new administration.

However, the EPA has two primary powers relevant to this prohibition. It can (1) determine how it chooses to enforce the CAA and (2) craft the guidance it provides to industry businesses that manufacture, sell, and distribute products that impact vehicle emissions control systems, so that they can do so while remaining compliant with the law. Speaking to the EPA's enforcement discretion, the agency further clarified its enforcement policy in November 2020 when it released an updated guidance memo regarding Vehicle and Engine Tampering and Aftermarket Defeat Devices under the CAA.

Enforcement: The EPA has a list of its top enforcement priorities, currently called the National Enforcement and Compliance Initiatives (NECI). The NECI list specifies the industries and regulatory programs the agency will assign resources to enforce against with a focus on perceived egregious violators of existing U.S. environmental law. In 2019, under the first Trump administration, the EPA included enforcement against aftermarket defeat devices on its NECI list. Why parts of our industry were targeted at this time is a separate conversation for another day, but the reality is, significant parts of the industry ended up on the EPA's "naughty list." In 2023, the automotive aftermarket was removed from the NECI list, largely due to the compliance measures SEMA put in place to demonstrate good faith efforts to sell emissions-compliant products (i.e., an increasing number of companies getting California Air Resources Board (CARB) Executive Orders (EOs) and/or SEMA Certified certificates). The automotive aftermarket remains off of the EPA's top priorities list, and we'd like to keep it this way!

Historically, the EPA's enforcement of the CAA has been inconsistent, including periods of time with very little attention given to mobile sources and other times when enforcement has been hyper-aggressive. Nevertheless, whether a business "feels" the EPA is currently looking elsewhere, risk cannot be eliminated.

The EPA can generally enforce the CAA for automobile emissions for an extended period, though the specifics depend on the type of enforcement action and the nature of the violation. For both civil and criminal actions, a five-year statute of limitations typically applies from the date of the violation, although there are ways to further extend beyond five years for criminal allegations. In the case of "diesel gate," the EPA looked back more than 10 years at Volkswagen's actions. Thus, short-sighted business decisions can have future consequences.

Compliance: The EPA's guidance for manufacturers and distributors of products that could impact a vehicle's emissions is gray at best. Agency guidance dictates that the sale or use of an aftermarket product is legal if there is a documented reasonable basis showing there is no adverse impact on emissions. While EPA does not currently offer its own certification process, it explicitly recognizes emissions testing that mirrors original manufacturer certification standards. The EPA, through third-party agreements, provides an acknowledgement of compliant products in other industries. Some examples are the Energy Star program for appliances and the EPA's "approved and authorized" RFG Survey Association comprehensive sampling program to assist refiners with certain fuel compliance obligations.

The SEMA Certified-Emissions program, through SEMA Garage, provides what we believe meets the EPA's "reasonable basis" test outlined in its November 2020 enforcement policy. We are currently working with the EPA to establish some kind of acknowledgement of SEMA Certified-Emissions to provide the necessary safe harbor for our manufacturers and, ultimately, their distributors and retailers to sell emissions-related products as the aggressiveness of EPA enforcement ebbs and flows. To date, no product that has received a SEMA Certification and is marketed and used as intended has been enforced against by the EPA.

However, as a result of previous EPA enforcement actions made against some in the aftermarket industry and the lack of a clear path to compliance, some retailers and distributors have been hesitant to carry emissions-related products for fear of significant enforcement actions by the EPA. Through our efforts to get the EPA to recognize SEMA Certified-Emissions, it would provide the first federal pathway to demonstrate emissions compliance that wouldn't involve CARB, which has been the de facto national regulatory authority, even though 49 states fall under EPA regulations.

Sadly, as those who have pursued CARB EOs know, pursuing a CARB EO can add six months or more of delay to the time it takes to legally bring a product to market. There needs to be a clearer and more attainable way for manufacturers to comply with laws and regulations in the 49 other states. This is the problem SEMA is trying to solve through its work to get the EPA to officially recognize the SEMA Certified-Emissions program.

But President Trump signed all these Executive Orders reversing regulations…

If you're wondering, "What do all of President Trump's Executive Orders and the EPA's responsive actions related to the automotive industry mean for aftermarket businesses," please keep reading.

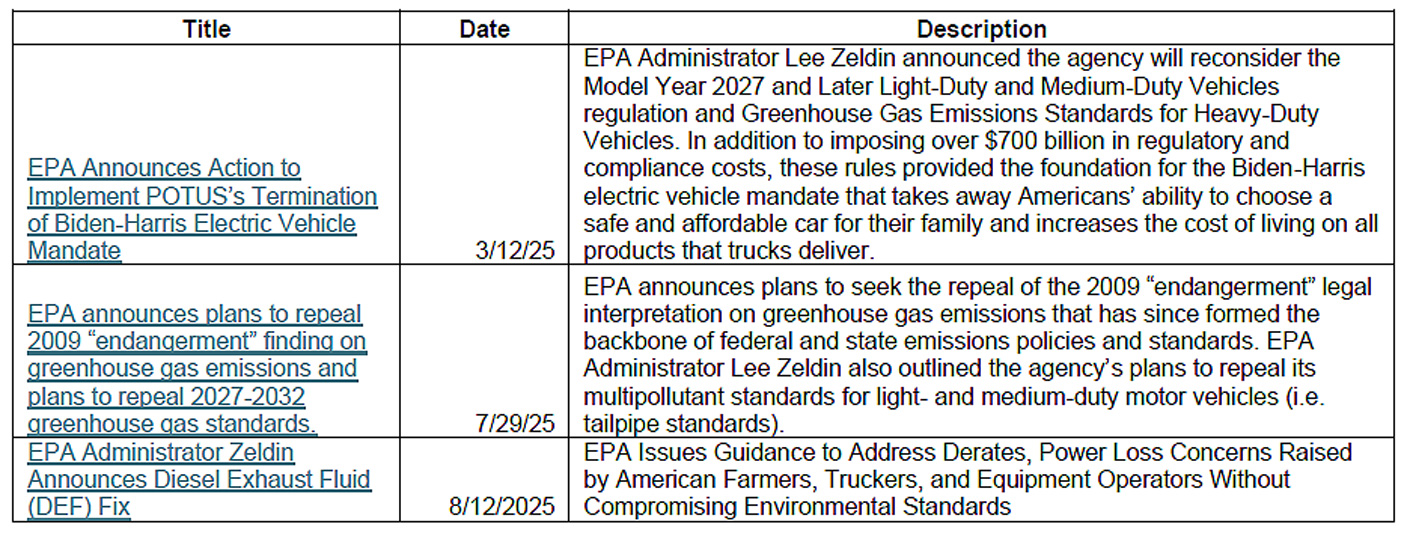

Regulatory Trickle-down Effect: Much of the deregulation in the automotive sector, to date, will primarily impact the OEs. The impact of these changes will trickle down to the aftermarket since regulations, like the EPA's draft rulemaking to repeal greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions standards for light-duty, medium-duty, and heavy-duty vehicles and engines will change what standards our products have to meet in order to be compliant with the tampering prohibition and the original OE configurations.

- Click here to learn more about the Trump Administration's plans to repeal the endangerment finding that was the underpinning for previous GHG standards.

Congressional Review Act: The most impactful deregulatory move is actually now a federal law. Stick with us here, because the Congressional Review Act (CRA) is a nuanced, procedural tool that allows Congress to stop the implementation of regulations within 60 days of a regulation being finalized (the CRA is a great check and balance tool). When President Trump signed into law the CRA resolutions earlier this year, the federal government reversed California's internal combustion engine (ICE) bans. It was the first time Congress had set boundaries that clawed back California's automotive emissions regulations since 1970. There are now multiple lawsuits regarding the CRA and California's engine bans ongoing in various courts. California, for example, has already sued the federal government over the CRAs that overturned California's waivers to institute ICE bans and other automotive restrictions approved by the Biden Administration.

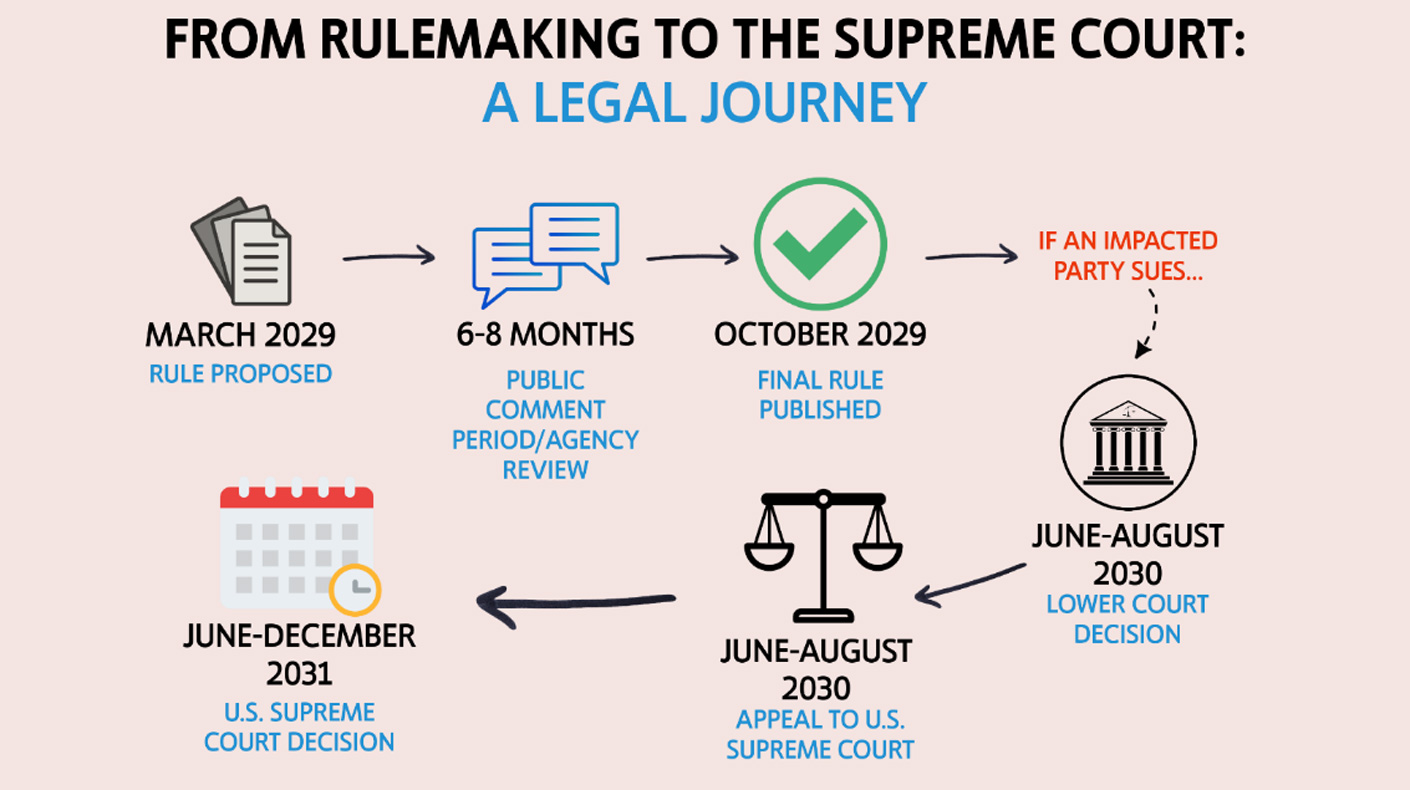

The outcome of those cases remains to be seen, but they will likely take an average of two years to make their way through the courts--so any finality to the CRA and other challenges to the deregulation agenda won't be settled until close to the end of the Trump Administration.

But the CRA may still stop California's electric vehicle mandates through 2028 and make California think twice about overreaching and attempting to set national policy through the limited exemption afforded to the state in the federal CAA. And because of the CRA, it may be more difficult for any future EPA to allow for California's overreach to pass muster in the courts.

Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh's opinion in Diamond Alternative Energy, LLC v. EPA included the following footnote:

In this opinion, we use the term 'invalidated' as shorthand to describe the result from setting aside EPA's approval of the California regulations. Under D.C. Circuit precedent, setting aside EPA's approval would mean that California may not enforce its greenhouse-gas emissions limits and electric-vehicle mandate for new vehicle fleets.1

End of the Chevron Deference. In the current state of affairs, environmental groups and the state of California will challenge more of the deregulatory actions. But the U.S. Supreme Court's 2024 decision to overturn what is called the "Chevron deference" also matters to the future of automotive regulation.2

The overturn of Chevron deference will play a significant role in any lawsuits regarding the President's Executive Orders and the Trump EPA's deregulation, as the courts will no longer be required to "defer" to a federal agency's interpretation if the underlying law, which was passed by Congress and is the basis for the regulation, is either ambiguous or silent. Any new regulations passed by a future administration will be subject to stricter scrutiny in the courts, but as mentioned above, remedying these challenges will not be fast.

What About the Post-Trump EPA?

Who controls the White House in 2029 and beyond will determine how aggressive the EPA's regulatory reach will be in the future.

Hypothetically, assume it's 2029, and there is a new president in the White House. This new president could have a more pro-regulatory agenda that reverses much of the deregulation currently happening under the current president.

To give you an idea of what a timeline for such a reversal could look like, here's a hypothetical example:

Product Development Strategy

As manufacturers of aftermarket performance parts develop future products, they should ensure that their emissions profiles, when installed on an OE platform, do not exceed the stock emissions profile of a vehicle when it is driven off a dealership lot. Remember, it is not about the additional power you create, it's about ensuring that additional power does not create additional emissions.

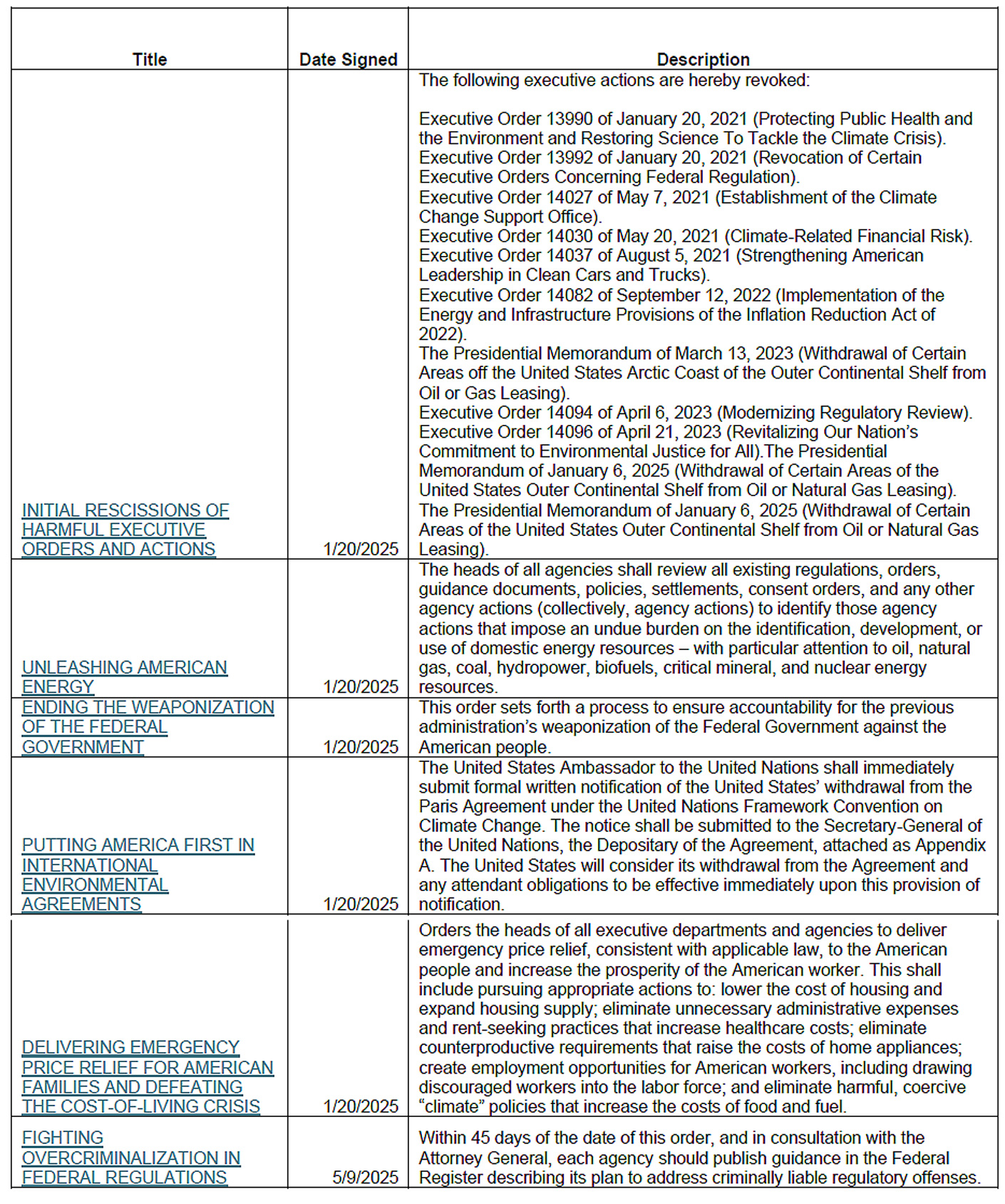

So, how do President Trump's Executive Orders and the EPA's actions to date impact the automotive sector?

Key White House Executive Orders

EPA Actions

The Role of the States

Under current law, each state can enforce the federal CAA or choose to leave enforcement up to the EPA. States can also enforce these laws at the consumer level.

The EPA and its enforcement actions in the last decade have largely been focused on manufacturers, distributors, and retailers because they were the easiest targets to identify, especially those businesses that have a large social media presence and sell their products online. The average consumer is much harder for the agency to find, and thus, EPA hasn't enforced against individual consumers, even though the agency maintains it has the authority to do so. But it doesn't make it any less illegal if a consumer chooses to take an emissions control device off their vehicle and still drive that vehicle on public roads.

There are two recent instances where states have decided to enact more aggressive enforcement against individual consumers. Nevada recently enacted a new law, SB80, which creates stiffer financial penalties on consumers who violate emissions laws. The state has always had the ability to enforce; they've just now decided to put more teeth into it. And it was not done to put the automotive aftermarket out of business in the state, but as a mechanism to enforce other illegal activity, like unsanctioned street takeovers that we've all seen on social media.

Anecdotally, we received word from another automotive group we work closely with that the State of New York conducted emissions checkpoints throughout the state to check for illegal emissions control tampering earlier this spring/summer. Again, New York has the authority to do this--and always has had that authority.

For Reference Sake

Emissions policy has a long history, and it's easy to forget how far things go back. Here's a helpful reference of the timeline and definitions that remain pertinent to today's discussions.

When did emissions regulations start?

Tailpipe emissions regulations started back in the '70s when there was a massive smog problem in urban areas of the United States. In the years leading up to the '70s, it was a fight for whoever could make the most horsepower. Fuel economy and air pollution were nonexistent conversations at the time.

What emissions are being discussed here, and why are each regulated?

- Carbon Monoxide (CO): A colorless, odorless toxic gas.

- Nitrogen Oxides (NOₓ): Contribute to smog and acid rain.

- Hydrocarbons/Non-Methane Organic Gases (HC or NMHC): Contribute to smog.

- Particulate Matter (PM): Microscopic solids that contribute to respiratory issues.

- Formaldehyde (HCHO): A toxic gas that is the byproduct of incomplete combustion. Fuel blends with higher ethanol content produce higher levels of CO.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO₂): Primary greenhouse gas to trap heat in and used by plants for oxygen production.

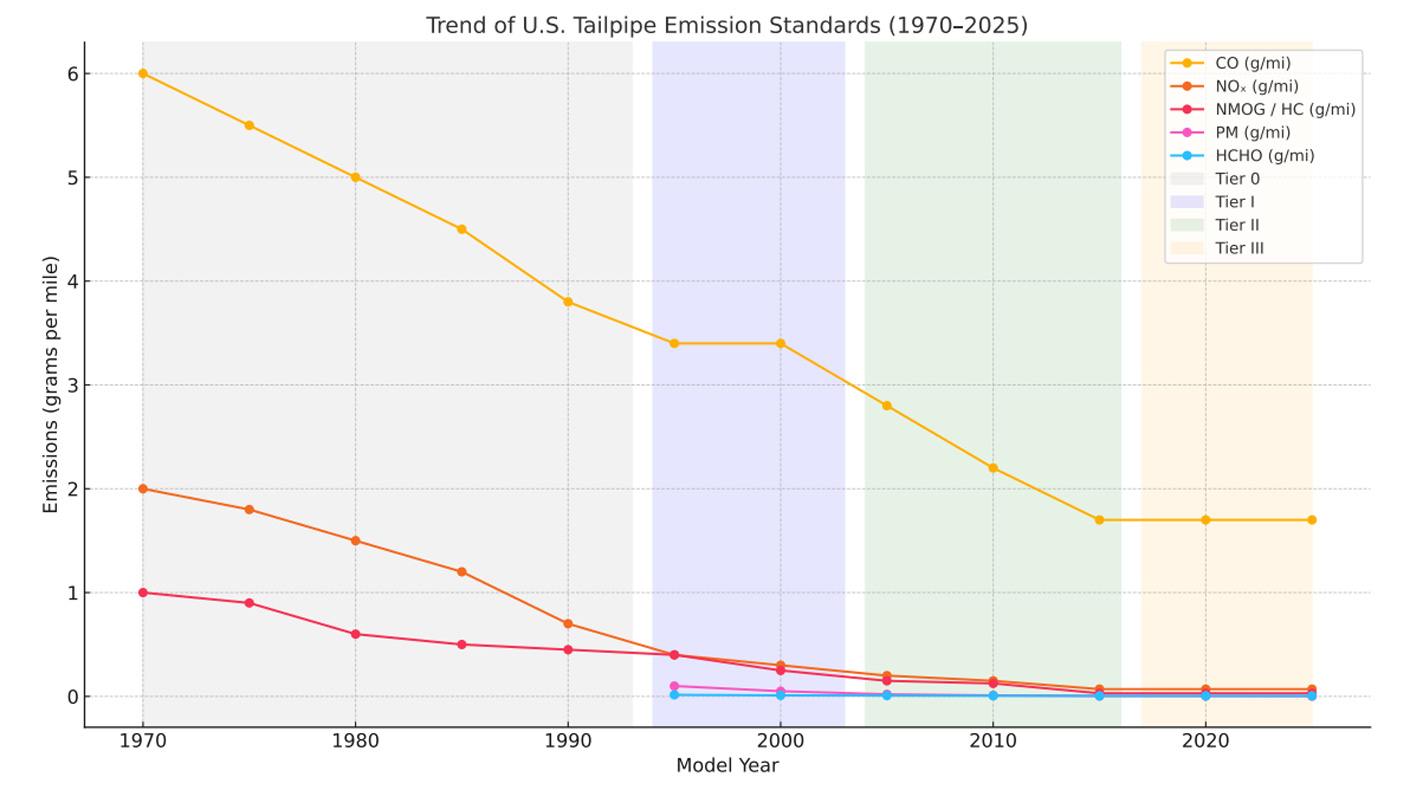

First, we are going to highlight key plot points in the federal emissions storyline. The implementation of the Clean Air Act is informally referred to as "Tier 0". However, the idea of "Tiers" wasn't implemented until 1994 with the introduction of "Tier 1".

"Clean Air" Timeline

1970: Clean Air Act Passed

- Landmark federal legislation mandating air quality standards.

- Authorized the EPA to regulate emissions from vehicles.

1971: First Federal Emissions Standards Implemented

- CO, HC, and NOₓ limits introduced for new passenger vehicles.

- Now known informally as the beginning of "Tier 0."

- Vehicles had rudimentary controls (Positive Crankcase Vent (PCV) valves, air pumps).

1975: Catalytic Converter was Introduced

- Required for most gasoline cars.

- Huge drop in CO and HC emissions (~80% reduction).

- Unleaded gasoline is introduced to protect converters.

1981: Three-Way Catalytic Converter Becomes Standard

- First tech to reduce NOₓ, CO, and HC simultaneously.

- Engine controls like Oxygen (O₂) sensors and fuel injection improve emissions precision.

1990: Clean Air Act Amendments

- Introduced tougher rules and specific deadlines.

- Required advanced tech and fuel reformulations.

- Set the stage for formal Tier programs.

1994: Tier 1 Standards Take Effect (Model-Year '94)

- First official use of the "Tier" classification.

- Nationwide emission caps on CO, NOₓ, HC, and HCHO.

- PM regulations introduced for some vehicles.

1996: On Board Diagnostics 2 (OBD-II) Required Nationwide

- Onboard diagnostics standardizes emissions monitoring across all brands.

- Required for all light-duty gasoline vehicles.

2004: Tier 2 Standards Begin (Model-Year '04)

- Introduced "Bin" system (Bins 1–11).

- NOₓ standards dropped from ~0.4 to 0.07 g/mi fleet average. (80% reduction)

- Sulfur in gasoline capped at 30 ppm to protect catalysts.

2007: PM Controls Required on Some Diesels

- PM limits tightened, diesel particulate filters (DPFs) become common.

- Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel (ULSD) mandatory.

2010: Full Tier 2 Compliance in Effect

- Most light-duty vehicles certified to Bin 5 or better.

- CO around 2.1–2.8 g/mi, NOₓ down to 0.07 or below.

Note: It is at this point that we reached a science term called the "law of diminishing returns," otherwise known as, "a principle stating that benefits gained from something will represent a proportionally smaller gain as more money or energy is invested in it."

2014: Tier 3 Final Rule Published

- Sets the stage for more aggressive emission cuts.

- Includes tighter NMOG+NOₓ limits, CO and PM drops.

- Bin 30 becomes target for 2025.

2017: Tier 3 Phase-In Begins (Model Year '17)

- NMOG+NOₓ standard: 30 mg/mi fleet average goal by 2025.

- PM limit: 3 mg/mi (lower than Tier 2).

- CO typically ~1.7 g/mi or lower.

2020: Most New Vehicles Below Bin 50

- Real-world emissions improve thanks to direct injection, advanced catalysts.

- Many manufacturers certify under Bin 30 or 50 even before deadline.

2025: Final Tier 3 Goals Due

- All new vehicles expected to meet full Tier 3 targets:

- NMOG+NOₓ ≤ 30 mg/mi

- PM ≤ 3 mg/mi

- CO ~1.0–1.7 g/mi

- Represents ~90%–99% reduction in pollutants vs. 1970 levels.

Many things were said about "bins." What does that mean?

"Bins", otherwise known as "certification bins", were structured and implemented to account for the practicalities of vehicle production and market demand, while still being able to move towards better emissions. Each subsequent number has slightly more lenient emissions standards than the previous number. Automakers can certify vehicles under any bin, as long as their fleet's average emissions meet the required target.

For instance, you would certify a vehicle like the '04 Toyota Prius in "Tier 2 Bin 2". You would then certify a '04 Toyota 4Runner in something higher, like "Tier 2 Bin 6 or 7", depending on the engine configuration. What this allowed was a popular model with undesirably high emissions to still be produced while not affecting the fleet as much as a straight comparison average would have done. This allowed manufacturers to maintain production and cash flow, while certifying the new models at the lower bins, then implementing the learned technology on the vehicles in the higher bin levels for the upcoming model year.

The chart above shows the measurable reduction in vehicle emissions standards over the last 50 years following the implementation of the Clean Air Act in 1970. Current policy discussions include the possibility of reverting new vehicle emissions standards to levels consistent with the model year' 14-'15 period. It was during this time that full Tier 2 compliance was required of all fleet vehicles.

This also marked the widespread adoption of diesel exhaust fluid (DEF) and diesel particulate filters (DPF) systems in diesel vehicles. These systems further reduced tailpipe emissions but also introduced an increase in CO₂ emissions due to the increased fuel consumption. Policy decisions that do not align with established scientific principles create engineering challenges for manufacturers, which can increase the cost of research, development, and vehicle production. Combustion of fuel to produce energy will always result in emissions.

While engineering can optimize systems within the boundaries of physics, those boundaries cannot be eliminated. Therefore, statements claiming that proposed policy changes will significantly worsen air quality disregard the documented reductions achieved by emissions control systems.

Separate from the pollutant regulations, the government has regulated fuel economy through the corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards for almost as long as the other tailpipe emissions. This is essentially a way to limit CO2 output by requiring that a manufacturer's fleet meet an average fuel economy for all the vehicles they sell, with some exclusions such as medium-duty trucks.

Since 2010, the standard has increased from 23.4 mpg to approximately 40 mpg in 2025. This is a dramatic increase and is targeted to increase to 49 mpg by 2026. This dramatic increase can only be met by OEMs adding electric vehicles and hybrids to their fleets. Now that Trump's EPA is questioning the research and data upon which these regulations were based, a rollback to more reasonable CAFE standards is anticipated.

Definitions

g/mi (Grams Per Mile): Used to quantify emissions gas amounts.

Mg/mi (Milligrams Per Mile): Used to quantify emissions gas amounts.

PPM (Parts Per Million): Used to quantify emissions gas amounts.

DPF (Diesel Particulate Filter): DPF works with diesel oxidation catalyst (DOC) to reduce particulate matter in diesel engine exhaust. The DPF traps soot particles, which accumulate over time and require removal through regeneration. Active regeneration occurs when additional fuel is injected into the exhaust, which then passes through the DOC and causes a chemical reaction that raises exhaust temperature enough to combust the soot. This process converts soot into gases such as CO and NOₓ, while ash remains in the filter. Passive regeneration happens when engine load causes exhaust temperatures to naturally reach levels sufficient to combust the soot without added fuel. Ash cannot be removed by regeneration and builds up over time, requiring the DPF to be cleaned or replaced to maintain engine performance and emissions control.

DEF (Diesel Exhaust Fluid): DEF is a mixture of 32.5 percent urea and 67.5 percent deionized water. It is injected into the exhaust stream after the DPF and before the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) converter. In the SCR, DEF reacts with high-temperature exhaust gases and breaks down into ammonia. The ammonia reacts with NOₓ in the exhaust, converting them into nitrogen gas (N₂), water vapor (H₂O), and carbon dioxide (CO₂). DEF is corrosive to many metals, absorbs moisture from the air, and degrades under ultraviolet (UV) light. It must be stored in airtight, UV-protected containers made of plastic or stainless steel to prevent contamination and maintain chemical stability.

Questions?

Please reach out to SEMA's Washington, D.C.-based Government Affairs team at governmentaffairs@sema.org with any additional questions. Our office will continue to provide these important updates to our members as the deregulation agenda evolves.

1Diamond Alternative Energy, LLC v. EPA, 606 U. S. 384 (2025).

2Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 603 U. S. 369 (2024).

Image courtesy of Shutterstock