By Drew Hardin

Photography Courtesy Petersen Publishing Company Archive

On February 9, 1964, the Beatles made their first appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” a performance that kicked off not just Beatlemania in the United States but what was then called the British Invasion. Suddenly, shaggy British music groups became the in, groovy thing. Pop music would never be the same.

Nearly a year earlier, another British invasion of sorts took place at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Colin Chapman, founder of Lotus Cars, brought two Ford-powered Lotus 29 race cars to the Brickyard for the 1963 500. One of them, driven by Jimmy Clark, finished second. Indy car racing would never be the same.

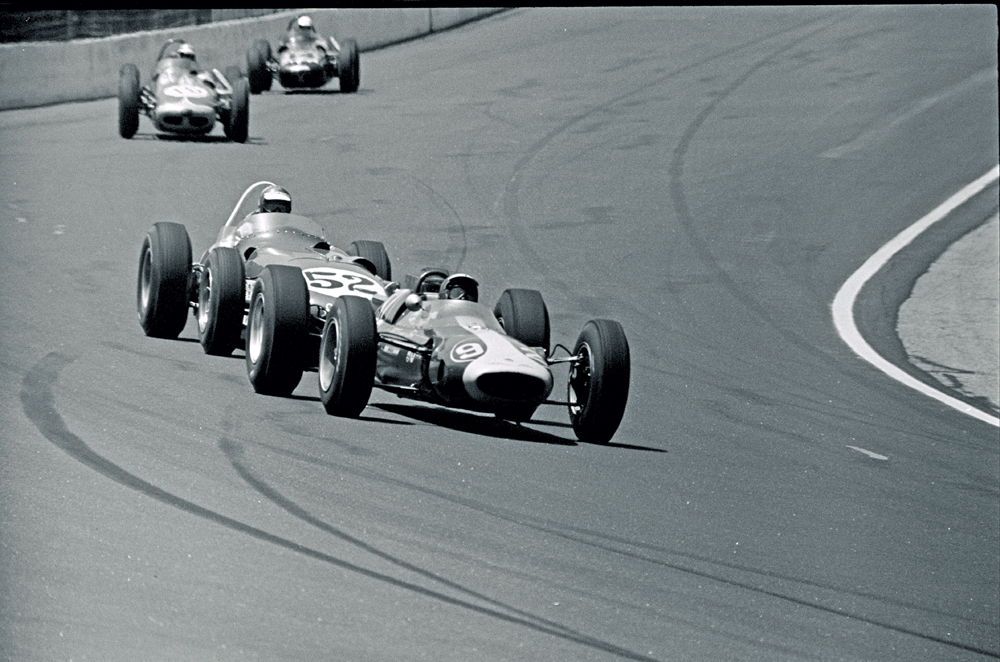

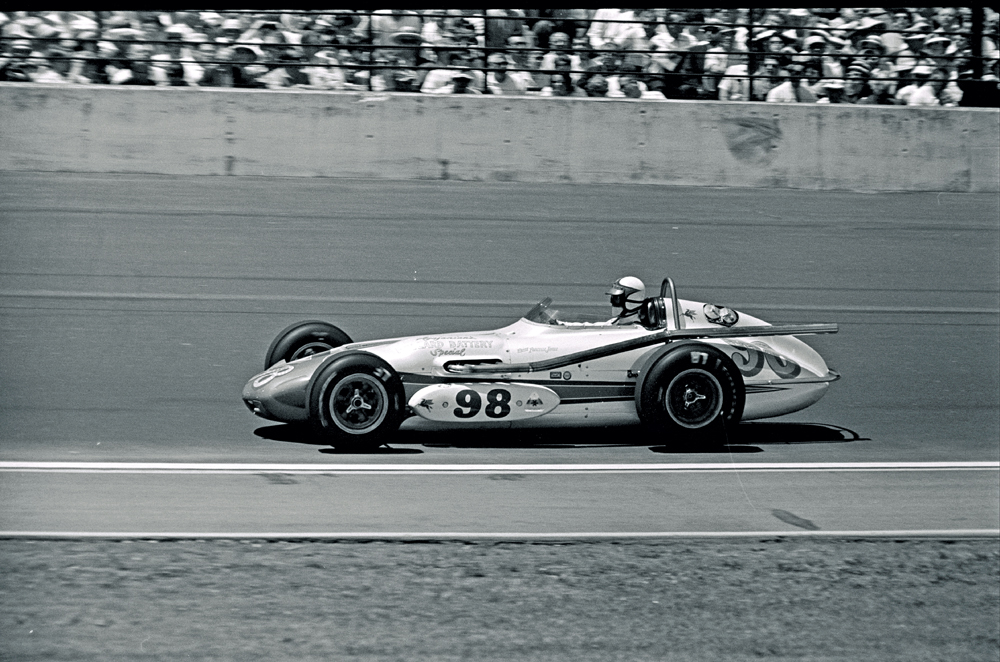

This was the era when competition at Indianapolis was dominated by Indy Roadsters. Built by Kurtis-Kraft, A.J. Watson, Eddie Kuzma and others, they were constructed from tube space frames clad with lightweight bodywork, fitted with beam axles front and rear, and were often powered by four-cylinder, dual-overhead-cam Offenhauser engines. By comparison, Chapman’s Lotus was low to the ground and tubular shaped, its engine located behind the driver.

The Lotus wasn’t the first to compete at Indy with this drivetrain layout. It wasn’t even the first British Indy competitor with that configuration. Jack Brabham drove a Formula 1-derived Cooper-Climax T54 to a ninth-place finish at the 1961 500. But the Lotus was the first to utilize Chapman’s innovative monocoque construction, in which “body and chassis become one with a stressed skin riveted overall,” wrote Hot Rod magazine’s Eric Rickman in the June 1963 issue.

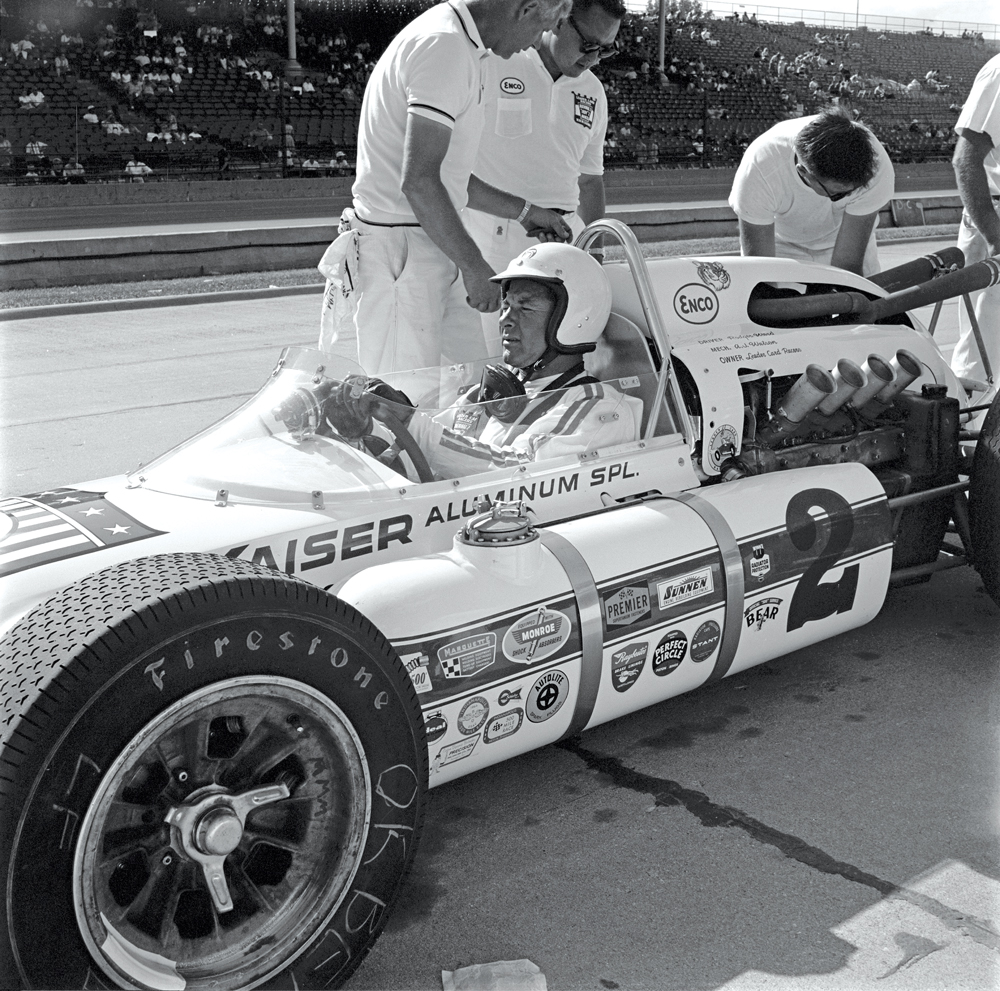

It also marked the first time “that an English car builder and an American factory collaborated to run at an event of this nature,” Rickman said. Ford supplied engines to Chapman—“an all-aluminum job based on the current Fairlane V8 engine”—with four Weber down-draft carburetors ingesting gasoline, not the methanol race fuel favored by other competitors. “Ford will admit to horsepower in excess of 350 at 6,000 to 8,000 rpm,” Rickman said. “The grapevine says it is as high as 370 horses on gas.”

An Offenhauser, Rickman noted, “puts out about 400 horses on alky, so it would appear that the ‘new breed’ is giving away a lot in the horsepower department.” Not so, he said. “They get it all back as free horsepower in greatly reduced frontal area and a much lower weight.”

Proof of concept came during testing in March 1963, when Dan Gurney turned laps in the Lotus/Ford at more than 150 mph—about the same speed Parnelli Jones hit to earn the pole position for the 1962 race. Gurney was a little slower in qualifying: 149.019, putting him 12th on the grid. Slightly faster was his teammate, Clark, at 149.75 mph, good for fifth on the grid. Pole position was again won by Jones, qualifying his Watson-built, Offy-powered “Old Calhoun” roadster at 151.153 mph.

Not surprisingly, this “new breed” of Indy racer generated controversy prior to the race. Some of it had to do with its tire and wheel sizes. Traditional Indy Roadsters used 16-in. wheels in front and 18s in back, while the Lotuses had 15-in. wheels at all four corners. Firestone “widened the smaller tires to regain track contact area,” wrote Ray Brock in his Indy 500 report for the August 1963 Hot Rod, which seemed to some in the “Offy camp” to be an unfair advantage. Despite demands by some teams, Firestone refused to withdraw the tires, stating they offered no advantage. Several drivers tested them and did not improve their speeds, but Jones went faster.

“The truth of the matter is that Parnelli is such a superior driver on the Indy track that he probably could have done the same speed on tractor tires,” Brock said. Yet Jones’ 153-mph lap speeds “opened the floodgates,” forcing Firestone and Halibrand to quickly ramp up production of the in-demand gear.

Jones dominated the 1963 Indy 500, leading 167 of the race’s 200 laps. Not long after his first pit stop, “track loudspeakers announced that Clark and Gurney were running one-two in the Lotus/Fords,” Brock reported. “A mighty roar went up from the spectators, and it was obvious that the sentimental favorites of the crowd were the small, low-slung cars with the high-pitched exhaust.”

Clark did lead the race for 28 laps—the most after Jones—and at one point late in the race came close to catching him but got caught in traffic during a yellow flag period. He finished 33 sec. behind Jones. Gurney finished seventh and likely would have done better, but after smacking the wall on the first day of qualifying, he had to leave Indianapolis for the Formula 1 race in Monaco and never had adequate time to sort out the Lotus backup car when he returned.

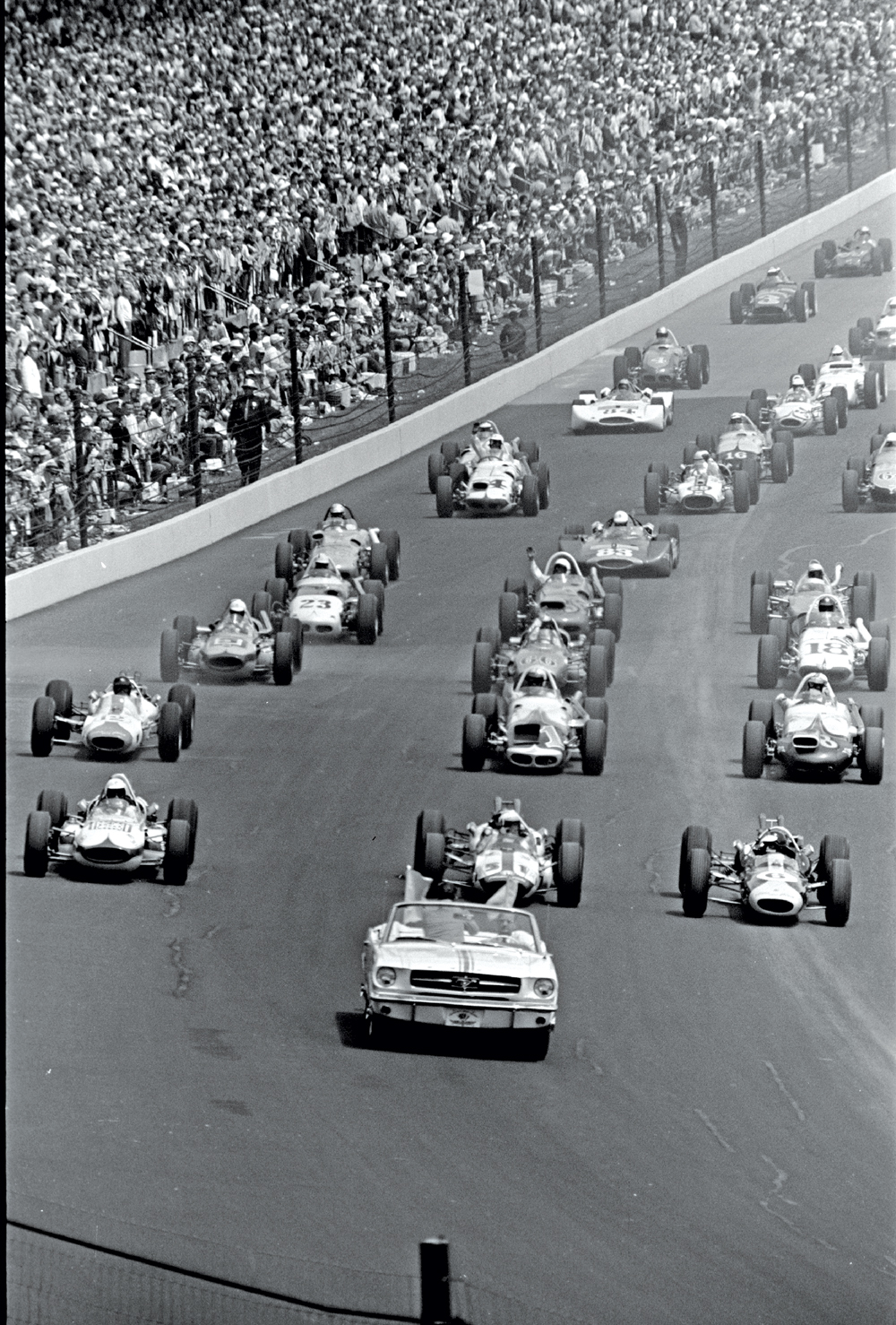

The impact Chapman and his Lotus/Fords had on Indianapolis racing became obvious when teams gathered at the Brickyard for the 1964 race. As Brock reported in Hot Rod’s August 1964 issue, “Ford-powered cars grabbed all three front-row starting positions.” Two of them were Lotuses, one was a Watson-built rear-engine car. Those performances pushed “America’s two best drivers, Parnelli Jones and A.J. Foyt,” down to fourth and fifth positions in their front-engine Offy roadsters. Clark’s pole-winning 158.828-mph qualifying speed was more than 7.5 mph faster than Jones’ pole winner the year before. At the end of qualifying, a full dozen of the 33-car field were rear-engine entries, seven with Ford engines, five with Offenhausers.

Several factors contributed to the jump in speeds between 1963 and 1964, Brock noted. The switch to lightweight chassis with independent suspensions played a role, as did Ford’s new engine, which produced 475 hp on alcohol fuel. But the single most important contributor was tire technology, he said. Firestone, which for years “had the Indy race to themselves,” suddenly had competition from Goodyear, Sears-Roebuck’s Allstate and Dunlop. Firestone’s Racing Division initiated an extensive off-season program to improve its Indianapolis tires; and by race day, almost all the entries were running Firestones, save for the Allstates on Mickey Thompson’s cars and the Dunlops on the Lotuses.

“Experts on the Indy scene” questioned Chapman’s choice, as the Dunlops showed a tendency to “chunk out” pieces of tread during practice, Brock reported. It would prove a fateful decision, as Clark’s rear suspension collapsed on the 47th lap, breakage caused by an imbalance of the left rear tire due to its losing almost a third of its tread. Gurney’s day wasn’t much better. An unscheduled pit stop early in the race slowed his pace; and when tire damage was noticed during his scheduled pit stop, Chapman decided to bring him in.

A pit lane fire sidelined Jones, clearing the way for Foyt to win the race. It would be the final time an Indy Roadster won Indy.

“The picture is now clear,” Brock wrote. “Rear-engined cars will dominate future Indy 500s. The roadster is through, but it’s still the champion.” A year later, Clark and Chapman celebrated in Indy’s winner’s circle after a lopsided performance that saw Clark’s Lotus/Ford lead all but 10 laps of the 1965 race.