FROM THE HILL

Behind the Scenes With U.S. Representative Bill Posey

Florida Congressman Tells SEMA News About His Racing Experiences

By Eric Snyder

Speedway.

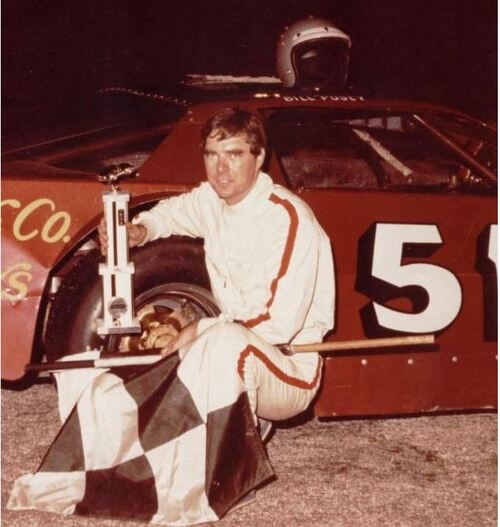

How many members of Congress have sold more than 100 racetracks, raced professionally, and have fought to reform government at the local, state, and federal levels? If your answer was one, you guessed correctly. U.S. Representative Bill Posey (R-FL) is one of a kind. He is a former racer, classic car owner, and has been one of SEMA’s strongest supporters since his days in the Florida State Legislature. When he’s not fighting to make the federal government more accountable and fiscally responsible, he’s working to advance policy solutions that benefit racers and automotive enthusiasts.

Rep. Posey serves as the House co-chair of the Congressional Automotive Performance and Motorsports Caucus, a position he’s uniquely qualified for given that he’s owned more than 30 race cars. He enjoys driving his ’66 Chevrolet Chevelle Malibu, ’57 Chevy stock tribute and ’30 Model A Ford Speedster when he’s back home in Florida. His daily driver is a ’15 Mustang GT. The Congressman is also an accomplished stock car racer, having received the Victory Lane Racing Association award for short track driver achievement in memory of Davey and Clifford Allison presented by Bobby and Judy Allison, Living Legends of Auto Racing, and other Hall of Fame awards.

Growing up in Southern California in the ’50s, the car culture was omnipresent. As a young boy, Rep. Posey started attending short track races with his father and riding his bike to watch older children race midgets. His family moved to the Space Coast of Florida, also known for its proximity to Daytona, when he was nine; his father accepted a position working on the Delta rocket. Rep. Posey witnessed the last Daytona race on the beach in 1958 and attended the next 10 Daytona 500s at the Super Speedway. By age 13, he started racing a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Rep. Posey purchased his first stock car at 15 and a ’54 Corvette when he was 16. He also raced a local businessman’s ’33 Ford with a fuel injected Hemi and a ’56 Chevy Gasser.

Hall of Fame Doug Evans (left) and SEMA President and CEO

Chris Kersting (right) present Rep. Posey with an award at the

2017 SEMA Washington Rally.

By his senior year at Cocoa High School, Rep. Posey purchased Mercury Astronaut Gus Grissom’s ’63 fuel-injected Corvette. Of course, he raced that too. After graduating from Brevard Community College with an Associate of Arts degree in 1969, he worked as an inspector for McDonnell Douglas on the third stage of the Saturn V Apollo rocket at the Kennedy Space Center but was laid off shortly after the Moon landing. While this period of transition ended his work in aerospace, it was the start of his career in real estate, including the buying and selling of racetracks.

At the age of 21 he was primarily racing at the Eau Gallie Speedway in Melbourne, Florida. When the track closed, Rep. Posey then formed the Mid-Florida Racing Association Inc. which bought, renovated and operated the speedway. Two years later he wrote the first book ever published about race promoting.

Rep. Posey heard the call to public service in 1974 when he was recruited to join the Rockledge Planning Commission. He was elected to the Rockledge City Council in 1976, serving for 10 years.

While Rep. Posey took a 12-year break from racing after the birth of his first child, he couldn’t keep away from the track and started to race again in the ’80s, primarily at Orlando Speedworld and New Smyrna Speedway.

He founded Posey & Co. Realtors and served as a Director of the Florida Association of Realtors and President of the Space Coast Association of Realtors. Continuing his ties to the motorsports industry, he established the National Racetrack Clearinghouse, which listed and sold racetracks in 35 states.

In 1992, Rep. Posey was elected to the Florida House of Representatives where he served for eight years before being elected to the Florida Senate in 2000. Despite his burgeoning political career, Posey continued to race late-models as a state lawmaker and began competing in classic race cars on dirt and asphalt in 2001.

SEMA started working with Rep. Posey when he was serving in the Florida Senate, where he was a charter member of SEMA’s State Automotive Enthusiast Leadership Caucus and sponsored SEMA-model legislation in 2007 to amend the vehicle titling and registration classification for street rods and create a new classification for custom vehicles. In 2008, he introduced legislation to provide an exemption from the commercial motor-carrier regulations for vehicles that occasionally transport personal property to a motorsports facility. Both bills were enacted into law. He also led the successful effort to reform Florida’s insurance laws to increase competition and lower rates and oversaw reforms to lower the cost of workers’ compensation, medical malpractice, and automobile insurance laws.

Melbourne, Florida, in his ’56 Ford.

When former U.S. Representative Dave Weldon announced his retirement from Congress in 2008, Posey once again heard the call to serve. He won a three-way primary for the U.S. House of Representatives and went on to handily win the general election. Rep. Posey currently represents the 8th Congressional District, which encompasses all of Brevard and Indian River Counties, and a portion of east Orange County.

Rep. Posey continues to be an excellent friend to automotive enthusiasts, racing, and the specialty automotive aftermarket in Washington. He was an original sponsor of the Low-Volume Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Act, which streamlined the requirements associated with producing replica vehicles. Rep. Posey worked closely with the White House and the U.S. Department of Transportation to advocate for completing the replica car rule in the final days of the Trump Administration. He is also an enthusiastic supporter of the Recognizing the Protection of Motorsports Act (RPM Act), serving as an original cosponsor of the bill during each session that it’s been introduced. As an accomplished racer, he is passionate about amending federal law to clarify the right to convert a street vehicle into a race car.

The Congressman is also a fierce advocate for reining in federal deficit spending and reducing government regulations. Rep. Posey serves on the Financial Services Committee and its two subcommittees on Consumer Protection & Financial Institutions and Housing, Community Development & Insurance. He is also a member of the Committee on Science, Space and Technology and its subcommittee on Space & Aeronautics.

Now, let’s go behind the scenes and hear directly from Congressman Posey.

SEMA News: What sparked your interest in cars and racing?

Bill Posey: It started when I was just a child. We lived in Encino, California, and my dad took me to what were then known as jalopy races at tracks in Culver City, Saugus, and other places around Los Angeles. I loved it, and we had a great time together.

I also used to ride my bicycle to watch the kids race midgets at a public park there that was about a mile or two away. It was exciting stuff. My one lifetime achievement that went unfulfilled is that I never had a quarter midget. Our family just couldn’t afford it. They were luxury items back in those days.

SN: Which classes of racing did you compete in?

BP: I started in the early model class at Eau Gallie Speedway. I raced there, on and off, from 16 until I was 21. I had a number of different cars, including a ’51 Ford, ’55 Chevy, two Hudson Hornets, and then a ’56 Ford, which was my best one, and I finally learned how to make these things work. Back in those days, a lot of performance products were homemade, including downdraft intake manifolds and headers.

I remember when I bought a cam for my ’56 Ford. It was a Crane cam. And if you go back to 1969, Harvey Crane was answering the phone. I told him what I wanted, referencing the lift and duration that the other guys were saying they were running, and Mr. Crane said, “I think you’re over-camming that thing for what you have in it. Send me your old cam, and I’ll regrind it for you.” Instead of charging $60 for new cam, he reground my cam for $25. And this was Harvey Crane!

North Turn Legends Beach parade at Ponce Inlet, Florida.

SN: What motivated you to become a racetrack owner?

BP: I wanted to race, and Eau Gallie Speedway was closed. The next closest track is probably 60 mi. away. The previous owner of Eau Gallie Speedway was just behind on his payments, and I just got laid off from the Apollo rocket program. I worked as an inspector on the rocket. Not long after we got a man on the moon, they laid us off because we already had the next three rockets pretty much ready to go. At that time, I was wondering if I could make a living in racing.

I blew up the engine on my car the last night the racetrack operated before it closed. The owner was in foreclosure, so I cut a deal with him and quickly formed a company. I was only 21 years old at the time.

I put together a business plan and ran the numbers for what I thought it should look like for six months. A buddy and I each put up $10,000, and I went to the owner of the racetrack. I said, “Listen, in 30 days you’re evicted from this place and you’ll have nothing. If you agree to put in your equity, we’ll each own a third of it. Let me go renegotiate this mortgage. I think we can pay it down with $10,000 and then have $10,000 to make some improvements.” He was impressed enough with the business plan that he agreed to it.

I owned the racetrack for about a year and turned it around. I promulgated a new set of rules that made sense. I had the first tire rule that I ever heard of in the country in 1969. Nobody else had tire rules anyone would want to have.

SN: How many tracks were you involved in buying and selling?

BP: In more than 40 years, maybe 100.

SN: What inspired you to run for office?

BP: I never saw myself involved in politics. I was in real estate and sold a friend a building lot, but the owner couldn’t get a permit to build his house because the city never dedicated the street. The city manager told me it’s the city’s fault, the developer did nothing wrong. It’s just a box they didn’t check, and he needed to check it before he could issue more permits. But one guy on the city council gave me a rash of baloney three times. I kept my mouth shut until after the thing was approved, and I shot back a wise comment to him. When I left city hall, a bunch of people followed me downstairs and said “it’s about time somebody stood up to that bully. You need to run for office.”

A friend of mine worked for Boeing and was on the council. He got a job promotion and moved to Seattle, so there was a vacancy and people encouraged me to run for it. I just started my real estate company, so my attention wasn’t on running for office. The day before the qualifying deadline, when I came home from work my wife Katie told me that, “three more people called today encouraging me to run.” So, we prayed about it. At the time I was thinking along the lines of, “if you want me to do that, you’re going to have to show me a way to do this that’s not going to be too expensive or too time-consuming.” Then I walked into the den and started opening the mail, and there’s a letter with no return address. Inside was a wanted poster for William J. Posey, like they put on the post office wall.

So, I decided to run. I drew up a poster with WANTED at the top. Under that it said “For Better Ideas” followed by my photograph and “REWARD.” The reward was my ideas about how to make government more efficient. I went down the next day to Village Printing and paid $100 to print up about 300 posters and filed for office on the last day. I came in middle of the pack, but I only had about 10 days to campaign before the special election.

A college political science teacher won, and I told him that he would always have my support if he did what he promised. After getting sworn in down at city hall, he gave some remarks and said, “It’s a good thing people didn’t elect Bill Posey blah, blah, blah.” He kept egging me on to run. So, a year later, at age 26, I spent $400 and unseated the political science professor. I served three terms. I promised my wife I would never run again. I was off for seven years, and they were the best seven years of making money, selling real estate, selling racetracks, racing cars, having a good life. I’ve been working as an elected official ever since.

at Orlando Speedworld.

SN: Why is the RPM Act so important to the future of motorsports?

BP: Well, if you don’t get interested in politics, you’re probably going to be out of business. That’s the bottom line. We know that our government tends to overregulate, including the automotive field. They also tend to be dishonest about it, as evidenced by the threat the RPM Act was initiated to defeat. They tried to sneak in rules saying you can never remove any pollution control devices even if it’s not for the street. I keep up to date on the bills introduced, but I don’t have a chance to read all the rules and regulations. Most people don’t know that rules are enforceable as laws, and rules are made by unelected bureaucrats. The Federal Register was 1 to 5 in. thick!

One of my big three goals in the Florida Legislature was to change the state’s Administrative Procedures Act, which I did. It took me eight years to do it. One of my goals was to change that up here, so that they couldn’t make laws they weren’t authorized to do. The EPA wasn’t authorized by any legislation to write a rule declaring it illegal to convert a motor vehicle into a race car, but they did anyway. Had it not been for SEMA, it would have been implemented. I didn’t catch it, nobody else caught it, because we don’t read the rules. The only thing we do about a bad rule, is to pass legislation to counteract it. It’s purely a matter of freedom. The omnipresent defenders of the nonexistent problems of the people never sleep!

SN: What can motorsports industry members do to better protect the future of racing? What can they do to make an impact?

BP: Get engaged. There are so many things on peoples’ plates right now between the pandemic, the border crisis, and the economic crisis. They don’t worry about automotive issues until they go to a car show or racetrack on a Saturday. It’s hard to keep it front and center.

If you’re worried about the defense of your industry, follow the SEMA Action Network (SAN). People need daily reminders, such as a decals on the back of their vehicle—maybe a sticker that says, “I vote motorsports rights!”

People need to understand. Performance automotive enthusiasts can’t sit on their hands hoping to be the last sheep eaten. Because surely, they will be eaten if they don’t take action and stop this craziness.