By Chris Shelton

If we’re not already at it, we’re likely near the cusp of an electric vehicle (EV) tipping point. Two years ago, the state of California mandated 35% EV sales by 2025 and banned all new non-EV sales by 2035; Washington state’s mandate is even more ambitious: by 2030 it will refuse to license any vehicle made that year or later unless it’s electric, a push that resembles the one in several Western European countries.

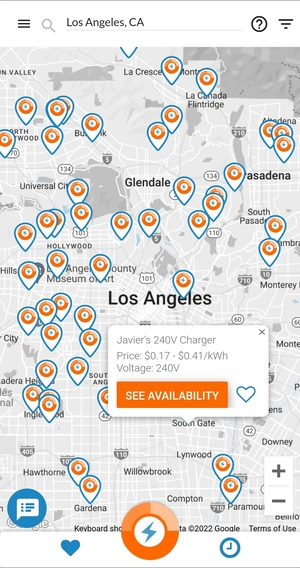

The future of charging for many Americans without access to their own chargers may look a little like this. Thanks to services like EVmatch, the public market has access to private, non-networked chargers and outlets, including 110V outlets that exist in every building in the United States.

Even the automakers are putting their eggs in the electric basket. Last year, GM announced it would ditch hydrocarbon power altogether by 2035. Ford hasn’t announced a similar mandate, but it’s pushing EU legislators to commit to all-electric new-car sales by 2035. Stellantis hasn’t set a mandate either, but says it hopes to go all electric by 2028. And perhaps most ambitiously, Volkswagen committed to 100% EV sales by 2026. As far as model-year introductions go, that’s only two years from now.

That’s music to the ears of EV advocates. But is widespread EV adoption possible within those timeframes? As strange as it seems, the answer is one that many EV advocates and adversaries agree on: Probably not. At least it’s not at the rate we’ve been implementing charging options in America, anyway.

Charge hosts can control the access to chargers. St. John’s Episcopal Church in Chicago opens its charger to anyone who books time. But hosts can specify who has access, effectively making a charger available to select users (i.e., residents of multi-unit dwellings). Photo courtesy: Brian Urbazewski

Charging Versus Fueling

The problem lies in the difference between the fueling and charging models. Whereas it takes only minutes to put a tiger in your tank, with current technology it can take hours to just partially charge a battery. That partly explains why more than 80% of EV charging happens overnight at home.

But that’s cold comfort for those living in multi-family dwellings (MFDs) like apartments and condominiums. Most existing MFDs can’t accommodate charging options required for mass EV adoption at the projected rate, at least not economically. And it’s no small problem, either; residents of MFDs make up nearly 30% of all households in America and nearly 50% in California, a state where only 18% of MFDs have access to EV charging. It gets even worse for lower-income drivers, most of whom live in communities dubbed charging deserts, a reference to an area’s lack of public charging options.

That’s changing of course. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed into law in November 2021 allocates $7.5 billion to “…accelerate the deployment of a national electric vehicle charging network.” Roughly $5 billion of that goes to build a nationwide network of 500,000 DC fast chargers along major transportation corridors that can charge some EVs to 80% in 20 to 30 min.

To give an idea of the scale of this project, consider that the United States had 177,433 gas stations as of May 2022. Should the program play out as planned, the number of commercial EV charging stations added to the grid by this bill would outnumber gas stations by nearly three to one. And that doesn’t include the 109,307 charging ports already in use.

Problem solved, right?

Well, it certainly helps. The network created by that part of the infrastructure bill facilitates long-distance travel by requiring at least four highway-accessible chargers within 50 mi. of each other. That presents at least two problems: for one, most people can’t or don’t want to stop alongside major transportation corridors for half an hour just to charge their car.

Whether accessed by a smart-device app or by a Web browser on a computer, EVmatch offers an experience like other Software as a Service (SaaS) such as dining, dating, and lodging apps. It compares users’ needs with host offerings to increase charging options in underserved areas.

Cost is another. “The shortcoming of fast charging is expense,” says Joel Levin, executive director of EV advocacy group Plug In America. “If you’re looking at people who live in an apartment that doesn’t have parking, they’re probably going to be somewhat lower income. And now you’re presenting them with the most expensive way to charge; the people who have the least money have the most expensive charging.” That part of the program may prove invaluable for driving long distances but not for daily use.

As Levin put it, the $2.5 billion remainder of the bill “focuses more on equity, underserved areas and charging deserts.” That funding will surely inspire countless solutions, like mounting chargers to existing structures as National Grid did in Melrose, Massachusetts. Seattle City Light made the system even more equitable by installing the pole-mounted chargers where residents request them.

Plug in America’s Executive Director Joel Levin maintains that widespread EV adoption depends on maximizing the potential in existing technology. “We have a survey that we do every year,” he says. “Among people who charge at home, about a quarter of them charge on 110.”

Installing chargers where potential users need them will certainly go a long way to encourage EV adoption. But it’s not likely to blanket the country with charging stations, at least not within the timeframes set by states and automakers. And if you’re even somewhat familiar with parking in major metropolitan areas, you know the frustration of trying to find any parking space. Now imagine trying to find one to charge your car. After a long day at work. And hungry.

It’s a situation that Vanessa Perkins knows well. She drives an EV. She lives in an apartment. And it’s in Chicago. “I noticed that there are a lot of neighborhoods that don’t have public charging,” she said, citing, among others, the one she lives in. “And if they do, it’s in a very expensive parking garage and you have to pay an entry fee.” So, she did some research and found a way to create more accessible and affordable charging. “It’s like a sharing economy,” she says.

What she found is EVmatch, a national peer-to-peer network where owners of private and commercial chargers can make their resources available for others to rent when they’re not using them. “Often we describe ourselves as the Airbnb of EV charging,” says EVmatch Founder and CEO Heather Hochrein.

“We provide a software platform for the web and mobile that allows individuals and businesses and commercial properties to rent out private charging stations to the public,” she continues. And Perkins’ nonprofit organization communitycharging.org, is one of EVmatch’s pilot programs. “It works anywhere a charger owner can open their charger to the public,” Perkins says. She calls the service transformative: Homeowners whose properties can accommodate guest vehicles let their neighbors use their vacant chargers via the service. Organizations like churches and businesses, whose lots go unused for big chunks of a day or overnight, are getting in on the program by building chargers for the communities they serve and offering them on the EVmatch network.

Charge-sharing pioneer Heather Hochrein has spent her career so far in the service of electricity technology. Her work in climate policy, extensive utility and management experience at Pacific Gas and Electric, and a senior leadership role at Rising Sun Energy Center, laid the foundation for EVmatch.

Levin says the challenge with charge sharing is to make the service consistently available. “To have an EV and not constantly be annoyed, you have to have a place where you can go once or twice a week. It’s there, it’s reliable, and it’s not going to be full. It needs to be consistent, not like you have to get on the internet and search for a place to charge every day.”

And that’s what distinguishes charge-sharing programs like EVmatch: potential users can book time on the charger. When the session ends, the user then drives off and opens the charger for the next user. More than giving users a place to charge, these bookable private charging stations give EV drivers a place to park. After a long day at work. When they’re hungry.

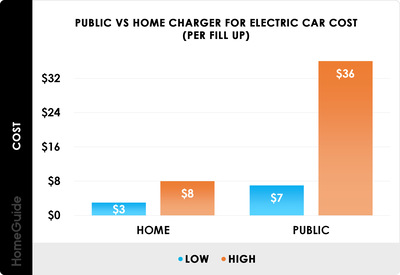

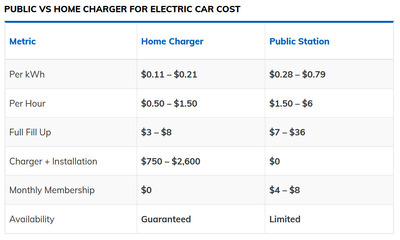

Access to affordable energy goes a great way to make electric vehicles viable for anyone who wants one. According to Homeguide.com, charging at a commercial station can cost upwards of 450% more than charging at home. Chart courtesy: www.homeguide.com

Elegance in Simplicity

Charge sharing differs from the typical commercial charging services offered by the likes of EVgo and Chargepoint. “Theirs is proprietary and top-down, infrastructure-heavy approach where you build and operate the charging stations,” Hochrein says. “You end up doing a lot of real-estate work like site selection, development and maintenance.”

And that translates to increased charging cost: due to the grid modifications and specialized hardware required to install one, DC fast chargers start at six figures. By contrast, a private Level-2 charger installation may cost only hundreds of dollars (a Level 2 can be as simple as a standard 220V receptacle). And almost every building has a Level 1 in the form of a conventional 110V wall receptacle.

“We have a survey that we do every year,” Levin says. “Among people who charge at home, about a quarter of them charge on 110.” It just takes longer.

Until now, the problem with using those non-networked chargers in a commercial application was the inability to meter and bill the user for the power consumed. Historically speaking, it took a smart charger to gauge how much current an EV consumes while charging and network connectivity to transfer that information for billing purposes. And EVmatch can in fact meter and bill that way. So far it has partnered with smart-charger manufacturers Enel X and Wallbox, and it’s working on other integrations using open-charge-point protocol communication.

But what distinguishes EVmatch is its ability to accurately estimate power consumption in the absence of a smart charger. “We have a tool where we estimate the cost of electricity,” Hochrein says. “It’s sophisticated in that it takes into account the vehicle, the charger power, the time of the day, and the utility-rate structure.” Users—either the general public or those the charger owner grants access—pay in advance for the duration of the charge. “So, they book, let’s say, a two-hour session and we know what car is charging,” she says. “We know the power output of the outlet or the charger. That calculator gets used to estimate the price and the driver pays for the session that they book. We’re using that software tool for the residential host, even if they don’t have a connected smart charger.”

EVmatch can also work with smart chargers to precisely measure current consumed and transmit information via the internet. So far, the company has integrated smart chargers from Wallbox and Enel X (Juice Box shown here). Photo courtesy: Brian Urbazewski

Overcoming the Challenges

The EVmatch model also has the potential to increase charging options in multi-family dwellings. The variables in installing chargers in those applications are numerous and sometimes daunting. Does the facility have spaces for every resident? Is the parking assigned or first-come? If the facility assigns parking, how does it allocate who gets a charger? How many residents drive EVs? Does every space need a charger? How do you bill the appropriate users for the power consumed? And can the structure bear multiple chargers without significant electrical improvements? “[If] every single parking stall has to have a dedicated charger, that massively overloads the infrastructure,” Hochrein says.

But charge sharing gives property managers the capacity to leverage their existing electrical infrastructure, including the load centers. “A lot of those panels can accommodate at least a few chargers as it is,” she says. “And so, with our software, we’re helping those property owners share those chargers more efficiently.”

It goes without saying that we need to build more chargers if we expect to adopt EVs on the massive scale anticipated by legislators and automakers. But no single answer will solve the charging issues that prevent mass EV adoption. As Joel Levin put it, “It’s more silver buckshot than silver bullet.” And as EV development begins to outpace internal-combustion engine development, new ideas and innovations like EVmatch’s charge-sharing program will likely prevail.

“We’ve done surveys among people who drive EVs—what their concerns are with charging, and they certainly have concerns,” Levin continues. But as Plug In America’s results show, those concerns are less about the number of chargers. “It’s the ability to access what’s already there rather than the lack of charging,” he says. “Sure, they’d like to have more charging. But they just want access.”

SOURCE

Community Charging

www.communitycharging.org

EVmatch

www.evmatch.com

Plug In America

www.pluginamerica.org