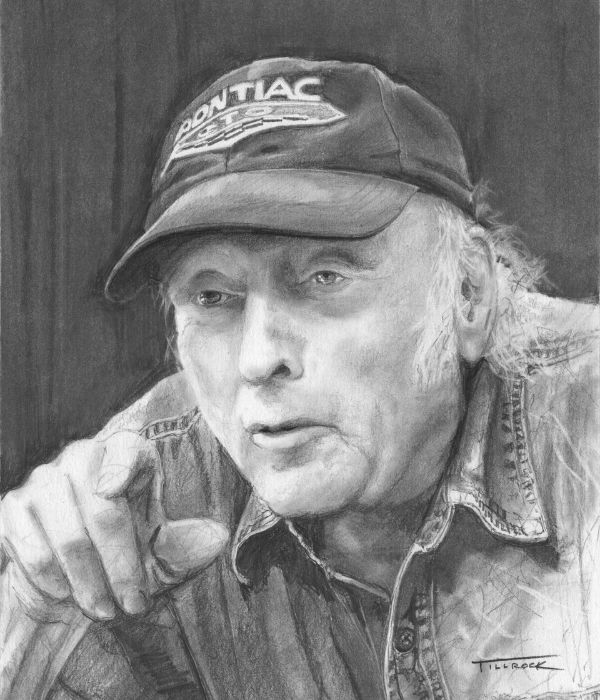

2023 SEMA Hall Of Fame Inductee

Steve Ames

Ames Performance Engineering

If you knew the late Steve Ames, it’s probably still difficult to imagine a world without him. Ames Performance Engineering (APE) wasn’t just another place for parts—it was a way to get close to the man. And if you owned a Pontiac, you wanted to be tight with him. Equal parts critical and honest, his word was bond. “Throughout the catalog we have quality notes,” said Kevin Beal, who joined Ames during one of APE’s numerous growth spurts. “What company would put under a product in the catalog, ‘Use only as a last resort’?”

Intending to follow in his father’s footsteps, Ames earned a mechanical engineering degree from Columbia University and landed a job at a paper mill, “which didn’t suit him at all,” recalled Joan Ames, Steve’s wife and co-founder of APE. He left to take a job as tech director at a local racetrack and repaired wrecks to make ends meet.

But, as Joan explained, everything changed in 1973. “We were going with his parents to Hershey, the big flea market,” she says. "He saw people selling parts that he had at home from the racing days. And he said, 'I got to get this stuff out and start selling it if it’s valuable.'"

More than making room and money, Ames learned the hidden value in obsolete parts. He joined the swap-meet circuit, rummaging through GM dealers’ back rooms during the week for stock to sell on weekends. “He would go on the road Monday through Friday, come home and sort out parts, and take them to a flea market and make money to go on the road the next week,” Joan remembered.

If there was a problem, it was competition. “We were Chevrolet and everybody else was too,” she recalls. But there was something different about Pontiac people. “He said, ‘You know…nobody hassles me about the price.’ So, a light bulb kind of came on and he said, ‘I’m going to make myself a Pontiac expert!’”

Through the ’70s, Steve roamed America’s backroads in pursuit of Pontiac parts. “But that ran out,” Joan admitted. “Everybody was hitting the dealers.”

Again, Ames pivoted. He leaned on his engineering background to pursue factories that could make small batch runs of the most requested parts. “We might want to make 2,000 parts; that was nowhere near enough for manufacturers in this country,” Joan said. But, as others were learning, Taiwanese factories were more than willing.

Ames distinguished himself by pursuing quality over profit. With factory examples of the parts as his gauge, he implemented a rigorous testing program. According to Joan, the only problem was in the minds of buyers: Initially they didn’t trust parts made in Taiwan. “We were kind of secretive about it,” she discloses. “Then after a while we just said flat out, ‘you can’t get these parts anywhere else.’ The quality [was] there, and they realized that it was.” In 1983, a decade after visiting that first Hershey meet, Steve and Joan published their first catalog. “We had a lot of what we call cottage-industry people [who] were making parts in their cellars, and we put those in our catalog too.”

Ames’ practice of delivering more than promised and his unrelenting pursuit to address market needs put Ames Performance Engineering at the forefront of the emerging reproduction industry. What began as a kitchen-table project grew to occupy the whole house, and Steve ultimately designed and built several multi-storey warehouses to fit the historic setting of his home across the road. The success gave him the opportunity to begin collecting low-production, rare option vehicles. In 1996 the focus changed to low-mileage (under 10,000), original, unrestored cars.

As the reproduction market blossomed in the early ’90s, so did legal issues. “It was scary to people like us,” Joan recalls. Following the lead of restorer and swap-meet promoter Jim Wirth [SEMA Hall of Fame 2004], they helped form a council specifically for businesses like theirs. The Automotive Restoration Market Organization (ARMO) found immediate traction in the licensing battles that threatened producers’ bottom lines. “SEMA and ARMO were always in the forefront of anything big in Washington,” Joan says. “I mean, it’s nice to know you’re not alone.”

As a councilmember, Ames contributed to numerous causes, including drumming up money for the scholarship fund that ARMO sponsored. “He liked that he never was president of ARMO,” Joan said. “He was more a worker bee. You know, ‘Give me a project and I’ll take it to the end.’ That was more him.”

In 2004, Steve and Joan sold Ames Performance Engineering to employee Kevin Beal and his cousin Don Emery. Steve continued to operate the wholesale/manufacturing business, Ames Automotive Enterprises (until its 2020 sale to Beal and Emery), and Ames Performance Classics, which now sells the NOS parts obtained in the ’70s and ’80s on eBay. In 2016, Steve and Joan established the Ames Automotive Foundation to give future generations a telescope into this industry’s past by way of nearly 100 examples. In 2018, ARMO, the council that Ames co-created, bestowed him its Lifetime Achievement Award. He passed from the scene in December 2020.

“You know, when Steve walked into a room, it just lit up,” Kevin Beal recalls. “He was right there in the trenches with you: He didn’t ask you to do anything that he wouldn’t be doing, and he’d be right there with you doing it.”